The regional Epilepsy Foundation works to raise awareness and understanding

Any time, any place and for any length of time — there is nothing predictable about when a seizure can strike.

For South Side resident Tajuana Jones, 36, who has epilepsy, the sudden and unpredictable nature of the condition she has lived with since she was 2 years old does not prevent her from enjoying life.

“Epilepsy is really never on my mind,” Jones said. “Why keep something like that on my mind? I already know I have it, so I’m just going to take my medicine, and that’s all.”

A person with epilepsy can experience more than 30 types of seizures, according to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Seizures are divided into two categories — focal seizures and generalized seizures.

Focal seizures, also known as partial seizures, occur in one part of the brain, and about 60 percent of people with epilepsy have these. Generalized seizures are a result of abnormal neuronal activity on both sides of the brain; they may cause loss of consciousness, falls or major muscle spasms.

Jones is affected by complex partial seizures — sometimes referred to as wandering seizures. When the seizure strikes, Jones said she might have something in her hand and will suddenly just drop it and wander around for a while.

Jones is affected by complex partial seizures — sometimes referred to as wandering seizures. When the seizure strikes, Jones said she might have something in her hand and will suddenly just drop it and wander around for a while.

“I’ll realize, ‘Oh my goodness, I was just with so and so, where did they go?’ That’s why they call them wandering,” she said.

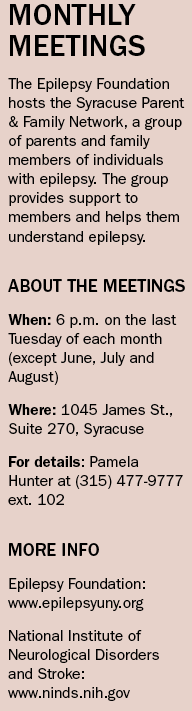

Pamela Hunter, regional director of organizational education and development at the Epilepsy Foundation, works to raise awareness about epilepsy. She said confusion about the disability can lead to stigma and fear of it.

“People don’t know that it’s not contagious,” Hunter said. “A lot of people think that a seizure always is when someone falls to the ground and has convulsions.” But not every person will be affected the same way.

The Epilepsy Foundation of Rochester-Syracuse-Binghamton opened in 1997 to serve the more than 5,000 people who have epilepsy in Onondaga and surrounding counties. The regional office provides education and first-aid training in seizures for members of schools, health and human service agencies and other groups. The foundation also offers free access to Emergency Medication Assistance programs for epilepsy patients.

The foundation is something Jones really likes, she said.

“I go to all the programs, and I think it’s something very educational with good service,” she said about the monthly meetings.

Epilepsy costs the nation more than $16.6 billion a year in health care and unemployment, according to a report from the National Epilepsy Foundation in 2000. To help with this, the Rochester-Syracuse-Binghamton foundation designed a program to assist those with epilepsy in finding employment or internship opportunities. The Kessler Foundation, a public charity organization, will fund the Employment Solutions Program through a two-year, $500,000 grant for the Syracuse office.

For now, Jones remains unemployed and receives Social Security Disability — benefits she signed up for with help from the Epilepsy Foundation. Jones said she plans to look for a job in social work so she can put to use her associate’s degree in human services from Onondaga Community College.

“I don’t mind working if I can do it,” she said. “That’s what I would prefer to do.”

Despite being on medication for her seizures, Jones said they are not under control.

“Every month, I’m going to have seizures, regardless of what medication they are putting me on,” Jones said. She estimates she has five to 10 seizures a month.

Life could be different for Jones. She would have a job if she didn’t have the condition. She would get a driver’s license. She would even learn to swim. But Jones said she doesn’t allow herself to live in fear of her illness.

Waking up wondering whether she will have a seizure that day isn’t something Jones ever does. “I’ve got a life to live, and I want to be happy,” she said. “I’m not going to walk around thinking about epilepsy all the time.”

— Tara Donaldson, The Stand’s staff reporter, contributed to this piece

The Stand

The Stand