Vice principal brings crisis plan to Dr. King Elementary School based on doctoral research

*Editor’s Note: This online version has been updated from the print story to reflect ‘Salaam Jennings-Bey’ in second reference and clarify a ‘popular’ student seemed to be valued over others

Quiet is the way Dr. Najah Salaam Jennings-Bey was described when she was taking her first course toward earning a doctorate in education. Others in the room were already top executives in their fields. She had little experience with literature reviews or conducting qualitative research. Even her professor recalls that by the end of that evening, he thought Salaam Jennings-Bey might not be ready to pursue such a prestigious degree.

But as she pursued her research on neighborhood trauma, a personal connection emerged. Her professors started to see the unique perspective only Jennings-Bey could provide because as a teen, she — herself — had been affected by homicides and violence.

As classes continued, Salaam Jennings-Bey stood out among her peers. She even represented her class as a speaker during graduation this past May.

“In the end, she didn’t just survive the program — she became a leader within it,” said Dr. Michael Robinson, her thesis adviser and site director of the Ed.D. Program in Executive Leadership at St. John Fisher College.

Many classmates revealed to Robinson how Salaam Jennings-Bey changed their perspectives by serving as an ambassador for her community and showing the strengths that exist within it. “She didn’t simply bring the community to the class,” he said. “She really took the class to the community.”

And the local community has shown strong sup- port for her as well. Salaam Jennings-Bey drew the largest crowd to ever attend a dissertation defense since the program began in 2006, Robinson said.

“There were at least 32 people there,” he said, noting that on average a defense draws three to eight attendees. “There are many in the community following her work.”

The sentiment is not lost on Salaam Jennings-Bey.

“Me being from the inner city and going to school to be a doctor — it’s big,” she said. “I’m living in the same neighborhood and experiencing the same type of community violence exposure as others. To see me overcome, it was joyous for my community.”

HER RESEARCH

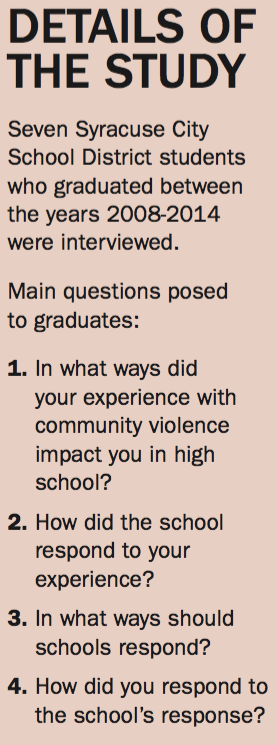

Over the summer, Salaam Jennings-Bey released her thesis as a book, “Urban Violence and Schools: Perspectives of High School Graduates,” to share students’ perspectives on how exposure to neighborhood violence affected their cognitive functioning in the classroom. Her qualitative study focused on seven Syracuse City School District graduates who had experienced the homicide of a friend, relative or close community member. The study gives voice to these students, who felt that their school’s response after a tragedy lacked support, sympathy and understanding.

Over the summer, Salaam Jennings-Bey released her thesis as a book, “Urban Violence and Schools: Perspectives of High School Graduates,” to share students’ perspectives on how exposure to neighborhood violence affected their cognitive functioning in the classroom. Her qualitative study focused on seven Syracuse City School District graduates who had experienced the homicide of a friend, relative or close community member. The study gives voice to these students, who felt that their school’s response after a tragedy lacked support, sympathy and understanding.

“I want people to know this research is not what Dr. Salaam Jennings-Bey thinks; this is what your students are saying,” she emphasized. “Their feedback can be used to help teach the teachers and administrators on how they can better serve our students.”

Another finding from her study: A gender difference exists in the way students grieve. Females shared that they want to be able to talk in groups, while males didn’t necessarily want immediate discussions.

“Females across the board said it would be most therapeutic to be pulled from class and to have a place where they could collectively go to grieve,” Salaam Jennings-Bey said. “The boys just wanted you to acknowledge that something has happened, ask them if they are OK and when they are ready, provide an opportunity to talk.”

Because her study focused on graduates of the district, she asked all participants what helped them complete school despite having experienced one or more traumas. She found four major contributing factors: having a support system, self-determination, staying active and memorializing the deceased.

What the students meant by memorializing is that completing high school was in memory or in honor of their friend — doing what they thought the friend they lost would have wanted. One female shared in the study: “When a person really close to you pass(es), it’s like what am I continuing for, and then you think about it … You do it because you think it would make that person happy and proud of you.”

What the students meant by memorializing is that completing high school was in memory or in honor of their friend — doing what they thought the friend they lost would have wanted. One female shared in the study: “When a person really close to you pass(es), it’s like what am I continuing for, and then you think about it … You do it because you think it would make that person happy and proud of you.”

FIRSTHAND EXPERIENCE

Growing up in a neighborhood rampant with crime and gang violence, Salaam Jennings-Bey experienced similar traumas as the students she interviewed. In high school, a friend was murdered. She herself has been shot (as a bystander at a party while in college) and stabbed (in the hand during a fight at a bar). While in college, her close friend was murdered by a boyfriend. In her foreword, she lists the names of friends she lost and also acknowledges those she calls “fallen angels,” whose deaths touched her participants. She even knew many of those victims personally.

“When students found out who was doing the study, it made it a lot easier for that population to be open and sit down with me,” she said. “I wasn’t just somebody coming from Syracuse University or Le Moyne (College), and they knew I understood what they were going through.”

As she sat with students, hearing their stories and even shedding tears with them, she says their feelings were the same as those she had 15 to 20 years ago. When fellow classmate Alex Williams was fatally shot in the back in Salaam Jennings-Bey’s freshman year of high school, she says she felt her school offered limited comfort.

“We would crack up on the bus every single day on our way to school,” she remembers. “Then one day, he was gone.”

When she arrived at William Nottingham High School the day after her friend was killed, she says then-principal Granger Ward held a moment of silence during the regular announcement.

“But that was it,” she said about the school’s response.

No conversations were held in the classrooms; no directive was given for students to seek out a counselor if they felt the need to talk or discuss their feelings, she said. “It was almost as if nobody cared,” she said about how she interpreted the school’s reaction.

“There was no direct process for me to talk about and receive help for what I was going through,” Jennings-Bey said. “Thus I suppressed it.”

Like her participants, she found support from her family and said staying busy with school helped her carry on.

BIOLOGY OF TRAUMA

BIOLOGY OF TRAUMA

When one experiences trauma from a sudden loss of a close friend or loved one, that stress is stored physically in the body, says Kate van Ingen Kelsen, a licensed therapist with more than 25 years of experience.

“It’s how our biology works,” she said. “Experiencing a trauma sets off an alarm system in our brains. Our heart rate increases, our blood pressure rises — your body gets ready for flight or fight. You’re not always conscious that this is happening. That’s just how our bodies are built to react.”

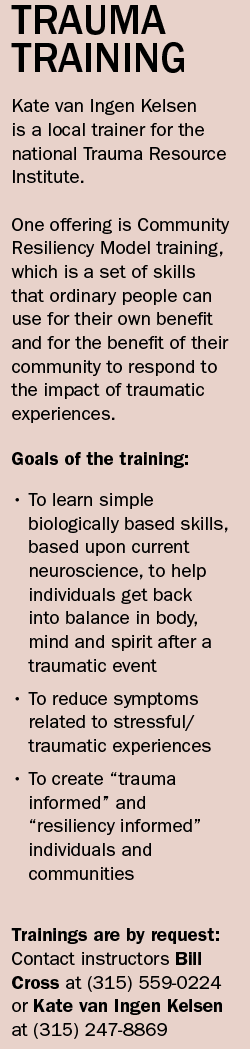

Kelsen has a private practice and works with Head Start as the educational center’s mental health coordinator. She also leads Community Resiliency Model trainings through the Trauma Resource Institute, whose mission is to help individuals understand the biology of traumatic stress and learn special skills to return themselves to balance.

“Those that have completed our training have told me they felt relief after learning what they were feeling was normal — that this is the way their body is intended to work,” she said.

Trainings are offered by request and have been given locally to fellow Head Start employees, mental health workers and even police officers. During the training, attendees don’t have to talk about the actual trauma. The focus is on learning how to recognize the body’s response and implement techniques to re-regulate one’s nervous system.

Kelsen says symptoms of exposure to trauma may include loss of concentration, acting out, aggression or withdrawal and hyper vigilance, which is an enhanced state of sensory sensitivity accompanied by an exaggerated intensity of behaviors to detect threats. This state also causes an increase in anxiety.

“Creating a sense of safety and connection is key,” Kelsen said. “Once these needs are met, for example, a high-school student could return to normal coursework and perform what is asked of them, but not until they have come back into their resilient zone where they can better handle ups and downs.”

ACKNOWLEDGING PAIN

Participants in Salaam Jennings-Bey’s study reported that teachers with whom they had close relationships offered emotional support individually, but that overall the school’s response was never unified and often insensitive.

One female shared in the study that when a popular student was murdered, the school gave comfort to its students for the day. But previous student homicides received little attention. The student stated in the study: “I think that after student X, they [administrators] should continue to do it … don’t do something once when you’re not going to do it for other people.”

In further discussions on how that student’s homicide was observed, Salaam Jennings-Bey heard from some participants that it appeared the school valued that student over others.

“I think the school districts should be taking a look at what students are saying because their story is the same story across the country,” Robinson said. “Administrators need to ask themselves: ‘What is our school’s response when there’s a tragic incident that takes place in our community?’”

HOW TO RESPOND

At Dr. King Elementary School, where Salaam Jennings-Bey has served as vice principal since 2015, she developed a crisis intervention team to first alert the staff that an act of violence has occurred in the community. Next, staff can work to identify any students who might be affected.

“Any time I hear that there’s been a homicide, I’ll alert the administrative staff and all the social workers and psychologists based at the school,” she said. “Then when we come to school the next day, I make sure staff and teachers are greeting students at the door, that we do a moment of silence, and I say the name of the family impacted to personalize it.”

By incorporating the students’ suggestions, the crisis plan she devised helps the school district be sensitive to students’ needs, she said, adding that schools should suspend regular coursework and provide avenues to address grief.

“After a neighborhood tragedy, teachers should be directed that the school is suspending regular day-to-day activities,” she said. “And as a vice principal, my expectation (of teachers) is that you have some kind of conversation with your (classroom) children.”

She says it is not her expectation that teachers serve as trauma counselors, but acknowledging that a tragedy has happened and asking students if they are OK is a simple way for teachers to show compassion.

“I think unfortunately, in education, we’re starting to depersonalize everything. We forget we’re in the human service business,” she said. “We don’t treat our children in the urban environment as if they were our own. Because if a child was your own and you knew that somebody they knew had been murdered, everything else would be secondary. Your first priority is to make sure that they are psychologically stable.”

— Article by Ashley Kang, The Stand director

The Stand

The Stand