Syracuse deputy mayor talks of diversification and revitalization

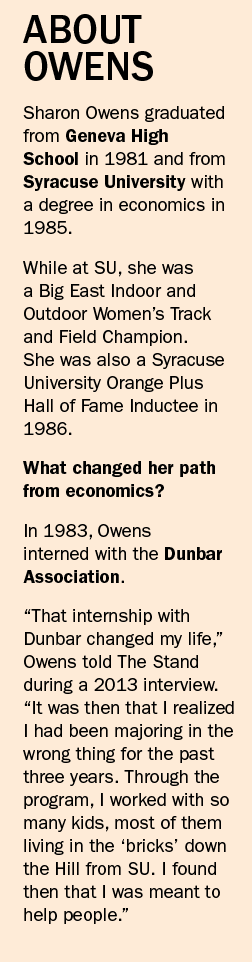

The Stand founder, Steve Davis, sat down for more than an hour with Syracuse Deputy Mayor Sharon Owens in her City Hall office. This is a lightly edited transcript of parts of that March 1 conversation. Owens, the former CEO of Syracuse Community Connections, ran the Southwest Community Center. She was named to Mayor Ben Walsh’s team in December. Owens previously worked in the office of the former mayor, Stephanie Miner.

Steve Davis: Can you give us a quick description of what the deputy mayor does?

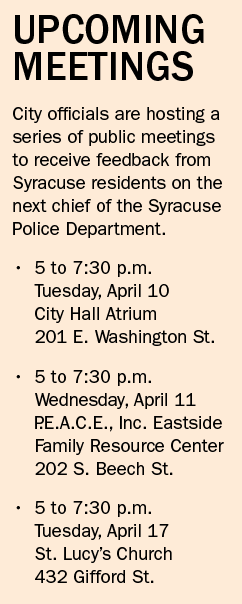

Sharon Owens: The title is deputy mayor, and I act in the capacity of chief of staff. I have direct reports: fire, police, neighborhood and business development and parks and recreation, and then I’m looking across the board at all of our departments. The biggest thing on my plate (now) is the search for the new police chief. What we’re doing now is nailing down the first phase of that, which is the community engagement process. We’re meeting with constituent groups geographically as well as special demographic groups. We’re just going to be meeting and meeting and meeting. We are going to look for an outside consultant to help with the search who’s done this on a national basis. The idea is to have someone on board by the end of December (2018) so when we come in in January (2019), we are starting with a new chief and Chief (Frank) Fowler leaves to get to go on to the well-deserved new life he has.

The good thing about being back is that most of the people are still here so you don’t have to spend the first two months figuring out where to go and who to talk to. We already know. And now we have a different perspective coming back. And there’s such an energy in the city. We’re hearing people ask, ‘Can we try this?’ Yeah, let’s try it! What do we have to lose?

ON SYRACUSE POLICE

SD: You have referred to community policing. Police are out in the community already. What does that mean?

SO: It takes it a step further. You guys (The Stand) do a great job of this: You engage that community in the reporting, so the reporting isn’t just about the community, the community is engaged in the narrative. Community policing has suffered because of budget cuts, so the closest we get to it now is community satellite offices. Westcott has one, Southwest has one, there’s an officer there so that the community gets to know that officer. But I remember when, all summer long, partner teams (of officers) would just walk up and down and the thing about that is that you get to know the people in the neighborhood, and the neighborhood gets to know you, and it’s not always perceived that you’re just driving through in a car that’s tinted up so that no one can even see your face. (With community policing) you don’t just become a symbol of a vehicle — just a car driving through the neighborhood — but you’re a heart-beating, blood-pumping human being walking in and talking to people to the point where if people are engaged in something you’ve gotten to a relationship where you know ‘Miss Smith’ and you know her grandson, and (you can say), ‘Look we’re going to talk to your grandmother.’ Because no matter who you are, how tough you are, there is somebody who you’ll listen to, and typically it’s grandma. Chief Fowler says this, ‘We’ve got to get cops out of the cars and walking beats, onto the streets. We’ve got to get them back in neighborhoods at community events, getting them in the parks and not in a car watching for trouble but walking around talking with people and engaging.’ And you know what, if I develop a relationship and I see you regularly in this location I might tell you a couple things about that street and that house in this situation.

(Chief Fowler) and I are also focused on making sure that we can diversify this next wave of cadets. The mayor made a commitment to 25 to 30, so that process is engaging now. We’re waiting for the list of eligible civil service candidates. So, I’m sitting with the chief saying, ‘OK I want to be immersed in this process to understand who is eligible and seeing how we can get that class diverse.’

SD: But only 10 percent of our police force is made up of minorities, while we are pushing 45 percent minority population in our city. The minority is almost the majority. The chief talks about how hard it is to find those minority persons who are interested in being a cop, because community members may not see them as a fellow minority on the force but just as someone in ‘blue.’

SO: Once you get enough people who are interested (in being a cop) we get to the other dilemma, which is the process. The process for me is we’re a public entity and civil service is the methodology for determining how you’re going to hire public employees. And the civil service law looks at the highest-tested people. And I don’t know about you, but I’m not good at tests.

What I’ve come to learn is that all of the candidates for law enforcement are under one civil service process that starts with the sheriff’s department. They tabulate an entire list of candidates who have taken the exam and have it available to any municipality in Onondaga County. And what the federal consent decree did for us is you can set a priority for minority candidates.

Fowler is looking at prioritizing those minority candidates. But after the test and before you get on the list, you have to pass the agility requirement.

Now, the chief says that (a number of candidates, including minorities) do get past the civil service test, but they don’t get past the agility. Being able to lift, being able to run, all of that kind of boot camp physical testing you have to go through — people don’t always make it through it. He’s told me stories of high school football players or basketball players that look like tanks — ‘Yeah, get help, study for the test, you’re big, let’s get you in there …’ — and then they did not pass the physical. Which was amazing to me, but it is what it is.

Then I would say the third leg of this is community engagement, for individuals who are interested, with organizations like Jubilee Homes, Alliance Network, ACLU, to help prepare people. There are individuals who are African-Americans who are coaches at different schools who will say, ‘I’ll do a six-week boot camp just to get people ready for that.’ Or there are a couple companies who will say, ‘Yeah, we can do an agility test and physicals and get people ready. But this is my business.’ Yeah, he’s not going to do it for free.

The chief is working on this, because this class is critical. It’s Frank’s swan song, it’s the priority of the mayor, and we’ve got to get this right. If you’re black and you grew up in the city of Syracuse, you are going to have affiliations, they’re probably at your family picnic, so you really have to look at the individual for the individual’s sake. This is Syracuse, you know, my mom and my aunt grew up in the same house. My mom raised us one way, my cousins were raised by their mom a different way. That doesn’t mean we don’t see each other, that doesn’t mean we don’t hang out on the weekend, but that doesn’t mean I do what you do just because you’re my family. We have to really home in on making sure people aren’t pre-judged by affiliations. You grew up with that guy, you went to middle school, high school, elementary school with that person. They went a route you didn’t go. The fact that you know them should have nothing to do with (how you are judged).

My god, what if we had more people on the street who actually knew the culture of the street? Not because they are engaged in the culture of the street, but because it’s their community.

ON SYRACUSE POVERTY

SD: What about work to revitalize parts of the city?

SO: The South Avenue study was started under the Miner Administration. The consultants are in town. … When Price Rite (grocery) was completed, we said the commitment with the investment of this company was, ‘What else are we going to do in the neighborhood?’ The ‘What else?’ is real. So SIDA (Syracuse Industrial Development Agency) took it on, and SIDA is funding the market study. With SIDA funding the study, to me it’s a model for every business corridor.

The heart-warming part of that whole (Price Rite) project for me is when I see people walking from that store with their bags. I am saddened for what happened with Nojaim (closing of that West Side supermarket), and I know there are many seniors in that high-rise over there. The Housing Authority has been amazing in coordinating bus routes to include Price Rite right now. What I did not like is the way neighborhoods were pitted against each other. For what purpose? … I was really disturbed by that. It wasn’t (owner) Paul (Nojaim) … It was entities who besides 9-5 (office hours in the neighborhood), they’re gone.

It took convincing of Price Rite by Walt (Dixie) and other people. In their market study, they already had a Price Rite on Erie Boulevard, so the typical market study would say that store (proposed for the South Side) would be too close. And I was like, ‘They are worlds apart. You’re worlds apart from the Tops. You’re worlds apart from the Western Lights stores. Folks who don’t drive can’t get there.’

I wasn’t sitting in this office at that time, but as the Southwest Community Center director, I was vehemently vocal about, ‘I’m not going to allow you to do that (pit neighborhoods). I just am not. I’m not. You know, letters to the editors and all that kind of garbage. Get out of here.’

I love planning. I love theory. You have to have it in order to strategically plan. But at some point, the plan has to hit the ground and people have to feel it, and touch it, and smell it and taste it. And that’s one of my roles here.

SD: What about the city’s relationship with Syracuse University under Chancellor Kent Syverud?

SO: Well, I think that with new leadership, you have different focuses and with (former Chancellor Nancy) Cantor her focus was physical investment in neighborhoods. The person in charge is hired by the (SU) trustee board and they’ve determined they want to take a different direction and do more research and more of that kind of thing and that, too, can benefit us. We had a great conversation with the law school because they were doing a symposium on poverty, and one of the best moves that this chancellor made was appointing Bea (Gonzalez) as community liaison. As soon as he did that, that spoke volumes to many of us in the community that his commitment was real because Bea is real. She was just here the other day with some staff. So, the conversations are happening.

I think the most exciting thing that people won’t see — can’t see because it is going on one person at a time — are conversations that are happening that may not have been happening.

I meet with county staff every week. And with the philanthropic and business community, we’re having ongoing conversations. You know people feel the window’s been thrown open, the door has been thrown open and they are coming in droves to say, ‘OK, what can we do, what can we do, what can we do? Let’s do this.’

With Syracuse University, the work you are doing around technology and systems integration, how can we use that as a municipality? How can your resources and your experts (help us)? We were talking about lead exposure, and we’re doing research and we’re looking at how we can address the lead issue in our housing stock and our commissioner now, Stephanie Pasquale is — because she’s from Boston — calling people in Boston, and the person there is saying the best researcher on lead is at SU, the best researcher in the country.

We’ve got folks in here for the South Avenue study, presenting to the mayor right now. So, it just is getting from the conversation to implementation.

We hope that the study will give us the baseline that we can talk to business about investment, and we’ll know what infrastructure we need to prioritize for South Avenue, we’ll know what the people who live around South Avenue are looking for. They talk all the time that we have no amenities. You know you got the world-famous Jerk Hut but you are limited. … That’s something neighbors have said, ‘Yeah you can get some great jerk chicken at the Jerk Hut, but what’s the marketing campaign to help the rest of city know that?’

SD: Are you still a part of the poverty initiative called HOPE (Healing Opportunity Prosperity Empowerment)?

SO: I am. As a matter of fact, we have a meeting this afternoon. We got running and got out in front of it. I always say this community was shamed into action. One thing about Syracuse, we are a prideful bunch of people, and I don’t know about you, but I am sick of all the negative stats. Our city is more than that. You know, something was just out that was funny. Someone posted that Syracuse is in the Top 25 of great places to live among cities our size. And, so, looking at it, Rochester and Buffalo are there, too, but when I looked at it, we ranked higher, and when I looked at why, it was interesting. It’s because you can get anywhere you want, quick. From here, you can get to Boston, you can get to Cleveland, you can get to Chicago, New York City, Canada. It’s a central location, and the potential is that central location.

Regarding HOPE, we got out there and we got momentum going, you know Helen Hudson and myself and Rita Paniagua came on and we hit the ground. We did so many community meetings and so many summits and all of that was to gather information. And then the ESPRI hit, which is the Empire State Poverty Reduction Initiative. So, the state says we have money, and Syracuse is eligible for the top tier of it, $2.75 million. So, here’s the money, but you’ve got to do all of this stuff. And that’s what slowed it down. We had to issue an RFP (Request for Proposals) because you have to show the state how you are going to spend the money.

So, we issued an RFP, we had applicants come in and now we are selecting applicants for initiatives that were proposed and would be part of the ESPRI initiative driven by HOPE.

But HOPE, for me, is not an initiative or a program. It has to be a movement. It has to be fluid enough to morph to whatever opportunities come. So, when the next ESPRI comes, HOPE is positioned to drive it.

ESPRI also required that we create an executive committee. That is the governing body for the money. The grantee is the United Way. The United Ways across the state are the grantees. Now there are some people who have said, ‘OK,’ and there are some people who hate that. Hate it. They feel that — I can only speak for this one — they feel that the United Way hasn’t funded the programs that really get to the people on the ground. But the United Way has to be responsible to its donors and set financial standards. While people do great work on the ground, they might not have the capacity to meet those (United Way) standards. Somehow, we have to fill that gap. Find a way to support people like Alamin Muhammad (founder of We Rise Above the Streets), who has garnered trust from a population that trusts no one, but he doesn’t have the capacity to sit down and write a grant for a million dollars or $250,000, financially manage it, write reports … he’s too busy feeding people. How do we fill that gap with an entity that can help manage that without him losing who he is? And the smaller guys are apprehensive of the larger guys because they don’t want to be assimilated and watered down into something bigger.

I talk to people (who say), ‘Well HOPE isn’t running programs.’ But that is not our purpose, to run programs. Our purpose is to look at the opportunities and the visions and the models and see how we can move the needle on poverty. The person doing the work is going to be somebody else. HOPE has to be a movement and the movement has to shift and change with the need. Poverty is a constant need, but how you address it changes.

That $2.75 million, this is the game plan from the state: ‘You communities in New York state (16 of them) have been identified by your data, and you get money depending on how big you are and severe your data is — your poverty is.’ So, we, unfortunately, hit the top threshold. The idea is that, ‘We’re giving you money to try some stuff, and in trying that stuff, our hope is that it’s going to be able to be replicated across the state.’

I’m like, ‘Come on, let’s award something, let’s get it done.’ Hopefully we’ll be able to get the awards out, get going with what really are pilots, pilots of, ‘This is what we think can be done to move the needle for people.’

SD: People might ID me — think of me — as a professor or a Baldwinsville resident … but when I think of Syracuse, often I see stories and conversations that define our residents as ‘poor.’ If that is a person’s identity, what does that do to him or her emotionally, psychologically?

SO: Poverty is defined by a financial standard by the federal government. But it is a living, breathing organism that affects your mind, body and spirit. It emanates from you as a person to your neighbor, your family and your community. By definition, it’s economic. So, when people say, ‘Well, you can’t throw money at it,’ I say that’s an oxymoron. It’s defined financially, so you need to get people work. But in getting people work, you also have to employ their sense of hope beyond the paycheck that, ‘Now I can achieve homeownership and I can achieve a college education for my children, and I can achieve being an active part of my community and changing the dynamic of my community one family at a time.’ But don’t tell me it’s poverty, and you can’t throw money at it. Bull. It’s defined financially. Defined!

I always said at Southwest, ‘You don’t know what you don’t know.’ I experienced the concept and the culture of work because I watched my parents go to work every day. I watched how they managed coming home after a bad day and venting with each other and saying, ‘This is how I process, so when I go back to work I know how to deal with it.’ I watched them call in when they were sick or schedule a family vacation and the whole dynamic of, ‘When is your time off?’ And, ‘This is when we can go and do something.’ I watched that. If you’ve never been a part of that experience, how do you know it? So, at Southwest, we had kids, their parents don’t work, their aunts and uncles don’t work, their neighbors don’t have a job. It becomes a culture. It becomes its own existence. It becomes a new normal that is not normal at all. It’s not normal. And that affects you. Not just financially, but physically: You don’t eat like everybody else eats, you don’t live in houses like everybody else lives, you’re probably walking around clinically depressed and you don’t know it because you don’t have time to deal with it. You are clinically depressed, while trying to raise your children.

I wish an artist could just listen to the stories of what poverty is and what it does to people and then render this monster, showing what it does to communities of people. It’s evil. It just is. It locks you down in a dark space. (But you’re thinking), ‘All I need is a crack to get to some sunlight. Give me the tools to find my way.’

One of the acronyms is ALICE, ‘asset limited, income constrained, employed.’ It’s a United Way acronym. ‘The working poor.’ I work one job, two jobs, maybe three jobs. I’m catching buses from one job to the next. You remember the story of the pregnant woman walking up to Jamesville (Correctional Facility)? There was an article about it. The woman is employed there, she’s pregnant. The bus stops by that senior home out on Jamesville Road, but she has to walk (several miles) to the prison, and she is still chugging her way to work. Or I’ve got to get my kids to school, school starts at 7:30 but work starts for me at 8, so I got to get them to school, then get a bus that runs on its schedule not mine, and then transfer.

I will never forget being on West Genesee Street and I’m coming east. I’m at the corner of Geddes. And a woman’s out there with these grocery bags, and it was starting to sprinkle. It was getting dark, about 7 o’clock. I roll the window down and ask, ‘Are you all right? Do you need a ride? Because we’re headed downtown.’ She says, ‘Yeah, but I’m not going that way, I’m going this way.’ She lived in the city, just inside the Solvay boundary, that’s where her apartment was. And (I think) she just moved there because she had a bunch of mops and cleaning supplies and that kind of stuff. She says, ‘Yeah I would like a ride but I’m not going your way I’m coming back, I live this way.’ And I said, ‘OK, why are you on this side of the street?’ And she said, ‘Because I have to catch the bus to the hub. The bus leaves the hub to go to my house at 9 o’clock.’

I’m like, ‘This is crazy.’

What do you do when you’re income-limited in a car-dependent community? When basically your ability to get somewhere shuts down at 10? And then most people in entry-level jobs work a swing shift. And then you deal with it in the winter we’ve been having this year, on top of that? What does that do to your psyche? And people say, ‘Well they just gave up.’ What the hell, yeah! They didn’t give up. They got beat down. You just get tired.

WHO IS SHARON?

SD: I’ve seen you mention your mom a couple of times. She must be really proud of you.

SO: She is. Very proud. The interesting thing is you know your parents as you’re growing up, but when you become an adult you begin to have a different kind of dynamic. You’re always their child but your conversations change, your perception of who they are changes, and it was then that I realized that my mother was a social activist. I never knew that. So, as we have conversations, as I became a woman, and particularly what I have done in my life, I know now that she missed the March on Washington (August 1963). She would have been there except for the fact that she was in the late term with me. And I’m like, ‘I so much inherited that from you. So, what drives me, and when I talk to her about who she is and what she’s done and the battles she’s fought for individuals and against systems, ‘Yeah that’s who you are.’ You know you get stuff from your parents but when I listen to her now as two adult women talking and then I realize now that her granddaughter, it’s passed on to her, too. And it’s just an absolute, you’re just there and you care about people and you just are indignantly mad when people are wronged. ‘What gives you the right to do that, to treat people that way?’ And I just always have tried to be a person that is going to try to be on the side of right. Getting to right, you might not agree with. But my ultimate goal is right.

The thing that this generation has figured out is that doing the right thing can actually be profitable. Just the dynamic in this world … even that campaign, being behind (candidate Walsh) and believing in who he is and what he wanted to do, was not the first benefit for me. The first benefit for me was all those young people of color that for the first time in their life got involved in politics and saw how it would affect day-to-day life and how it really meant something to them. And they’re still off and doing their thing. They’ll call and say, ‘Sharon, we got this idea.’ And I’m, ‘Tell me how you need me. Do what you’re going to do.’ I have the privilege of being the commencement speaker at Cazenovia in May, and someone was saying, ‘What are you going to talk about?’ It was, ‘You guys are poised and you get it.’ Helping and benefiting humanity and driving industry and making money doesn’t have to be two isolated occurrences. You have figured that out and don’t let anyone turn you away from what your brilliance has figured out. Helping the world and humanity helps your bottom line. It does. It’s a win-win. We don’t get many of those these days.

THE POWER OF SOCIAL MEDIA

SD: The digital world has helped. You don’t need a lot of people to get your message out.

SO: One thing about the campaign, I kept up to date every moment with what was going on because I got on Facebook. Now, social media has a good and a bad. The bad, what we see day-to-day particularly with young people, is the instant gratification of emotion. When you and I were growing up, if I’m mad, I’m going to call someone and tell them and give them a piece of my mind. I had 10 digits to change my mind, or even seven because you didn’t need an area code. I had seven digits to change my mind. And maybe by digit five I changed my mind and I hung up the phone. Now you ‘bah, bah, bah’ on social media and hit ‘send.’ You can’t take that back. It’s out there.

SD: And with the phone you’re telling one person, not the whole world.

SO: I had this conversation with my daughter. I said, ‘Everybody in the world doesn’t need to know every emotional roller coaster you go on. I’m (angry) and I post it. OK, in two hours you are not going to feel like that. But it’s gone now.’ My parents would say, ‘Don’t tell your friends all of your business.’ It might go from that person to that person to that person. In our circle, it might get to 10 people. (But today), you just posted it on Facebook. It’s been shared 55 times.

On the other hand, you’ve got a man sitting in a car with his girlfriend and telling the cop, ‘I have a licensed weapon, officer,’ and the world sees (streamed on Facebook) that he’s murdered. … That’s Philando Castile.

— Q&A and photos by Steve Davis, The Stand founder

The Stand

The Stand